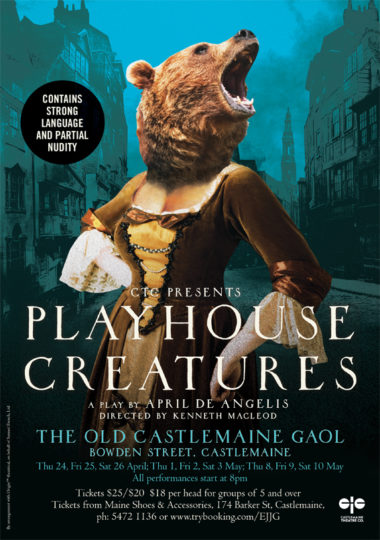

Directed by Kenneth MacLeod

with (in order of appearance) Kate Stones; Zenith Flume; Tiffany Naughton; Donna Steven; and Bridget Haylock.

A contemporary script by April de Angelis about the very first women actors to perform on the London stage during the Restoration period – the reign of Charles II in the 1660s.

ABOUT PLAYHOUSE CREATURES

“ ‘tis as hard a matter for a pretty woman to keep herself honest in the Theatre, as ‘tis for an apothecary to keep his treacle from the flies in hot weather – for every Libertine in the audience will be buzzing about her Honey-Pot.” Thomas Brown, 17th Century writer

London, 1669 – Bon vivant and culture vulture Charles II has restored the monarchy to England after decades of puritanical Commonwealth rule under Oliver Cromwell. He ushers in an era of unprecedented religious tolerance, artistic freedom and cultural enlightenment. One of his first bold moves is to permit women to tread the boards of London’s theatres for the very first time.

Join us backstage at the King’s Theatre, to witness the precarious lives of four of London’s most famous early actresses, as their trajectory rises from the gutter to the stars and back again. The most notorious amongst them is the riotous Nelly Gwyn who goes on to become the King’s favourite mistress…but sadly not all are as fortunate as she….

Historical Context

First performed in 1993, Playhouse Creatures, by English dramatist April D’Angelis, offers a darkly comic glimpse into the lives and careers of some of the first actresses granted licence to perform professionally on the English stage. Set in London during the period which became known as the English Restoration, Playhouse Creatures brings together four of the period’s first women of the stage – Mary Betterton, Rebecca Marshall, Elizabeth Farley and Nell Gwynne – in a colourful portrait of late 17th century theatre.

Prior to the reinstatement of the Catholic monarchy in 1660 under Charles II, England had endured eleven years of rigid social and religious Commonwealth rule under Oliver Cromwell. All theatres had been closed or destroyed well before Cromwell succeeded in taking power, with puritan Protestant sentiment deeming all ‘’entertainments’’ to be a threat to public order in such troubled times.

Having spent the years of Commonwealth rule living it up in self-imposed European exile, upon his return to the throne, pleasure-seeking aesthete Charles II immediately sought to reignite the cultural passions of English society, issuing Royal Patents to two of his staunchest followers to open new theatres. Given exclusive rights to stage plays for profit, the King’s and Duke’s companies were formed in London’s West End, creating an impenetrable duopoly and becoming fierce rivals for the patronage of largely aristocratic audiences.

Up until the closure of English theatres in 1642, all women’s parts had been played by ‘boy players’. While in exile, Charles had developed a taste for a more sophisticated European style of theatre, and was particularly beguiled by the sight of women on stage. In late 1660, Charles II issued a proclamation that all women’s roles would henceforth be performed women. The impact was immediate, with curious audiences turning out in droves to witness the spectacle of women on public display.

The presence of actual women on stage brought an expectation of eroticism, and contemporary playwrights were quick to exploit an actress’s obvious charms. “Couch scenes” in which an alluring young actress would be placed centre stage on a bed or couch seemingly asleep and in a state of undress became commonplace. Rape scenes also became a prominent feature, allowing female characters to retain their virtue whilst gratifying an audience’s desire for sexual titillation. “Breeches” roles which required women to dress as men also became popular, giving audiences an opportunity to admire a shapely leg sheathed in tight leggings.

Not surprisingly, this blatant objectification of women on stage served to fuel the widespread assumption that any woman who chose to display herself on a public stage was most likely a “whore”, and it was widely considered that acting was a profession which no respectable woman would ever pursue. In Playhouse Creatures, we see how the culture of the court helped to fuel the boorish behaviour directed at actresses. Charles II himself took orange-seller turned actress, Nell Gwynne, as one of his many long-term mistresses, eventually persuading her to abandon a highly successful career in favour of a townhouse, and later two children and a fatal dose of syphilis. Rebecca Marshall, whose story is also explored in the play, twice took her outrage at the treatment she received at the hands of various earls and gentlemen to the King, hoping to secure protection from unwanted advances.

At a time when we take for granted the rights of women to perform, write and direct; to own and manage theatres, Playhouse Creatures offers a lively account of the ways in which Restoration actresses fought for financial independence and the right to be respected as legitimate actors.

Please be aware that Playhouse Creatures contains some adult themes, earthy language and partial nudity.